I did not cross the Atlantic because I had always wanted to.

I crossed after my life collapsed.

Home, work, relationship—gone within a short span of time. The future no longer organised itself in front of me. I remember a sense of standing in the ruins of something I had assumed would hold. My nervous system did not look for meaning. It looked for movement.

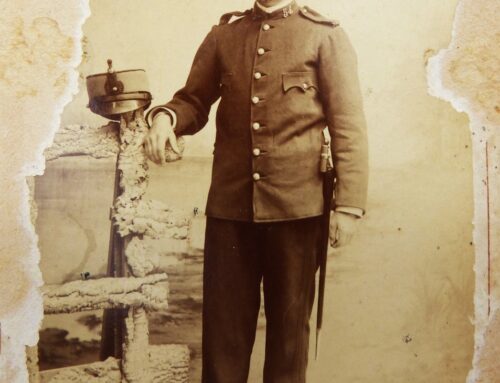

I did not know then that my ancestors had crossed the same ocean under very different circumstances. I did not know that in 1685, men from the same part of Somerset I came from were executed, whipped, or sold into slavery after the Monmouth Rebellion. I did not know that some were transported to the Caribbean, packed into ships, cut off from home, family, and any possibility of return. I only knew that staying felt impossible.

So, when the chance to sail appeared—suddenly, improbably—I did not question it. My body recognised the invitation before my mind could catch up.

The boat was large and unreliable. The engine barely worked. There was no radio. Navigation depended on the sky. The Atlantic was not gentle. Waves rose and fell like moving walls. Sometimes we were carried; sometimes we were held in stillness for days. Food ran low. Matches became precious. The wind decided everything.

And yet, something in me began to settle.

The constant motion did something my nervous system could not achieve on land. The rhythm regulated what had been shattered. Fear and pleasure recalibrated themselves. Identity loosened. I became someone simpler: a body that watched the horizon, responded to weather, slept when it could and trusted the vessel to hold.

Only much later did I learn that several generations before me, men with my family names had made a similar crossing—not by choice, not with hope, but as punishment. Their lives had collapsed, too. Staying had not been an option for them either.

Nervous systems do not remember events. They remember what worked.

When structure disintegrates completely, when identity dissolves, and the future cannot be imagined, departure may be the only remaining form of regulation. For my ancestors, movement across water was forced. For me, it was offered. But the pattern was familiar enough.

I did not repeat their suffering. I did not reenact their trauma. What I did was cross under different conditions—fed, accompanied, with the possibility of arrival. Something unfinished was allowed to complete itself.

Afterwards, the urgency disappeared.

I did not feel the need to sail again. The pull was gone. Life reorganised slowly, quietly, in another place. The crossing receded into memory without demanding explanation.

Only decades later did I ask whether the journey had been personal at all.

Perhaps the nervous system sometimes reaches back—not to repeat the past, but to find a way through the present using the only maps it has ever known.